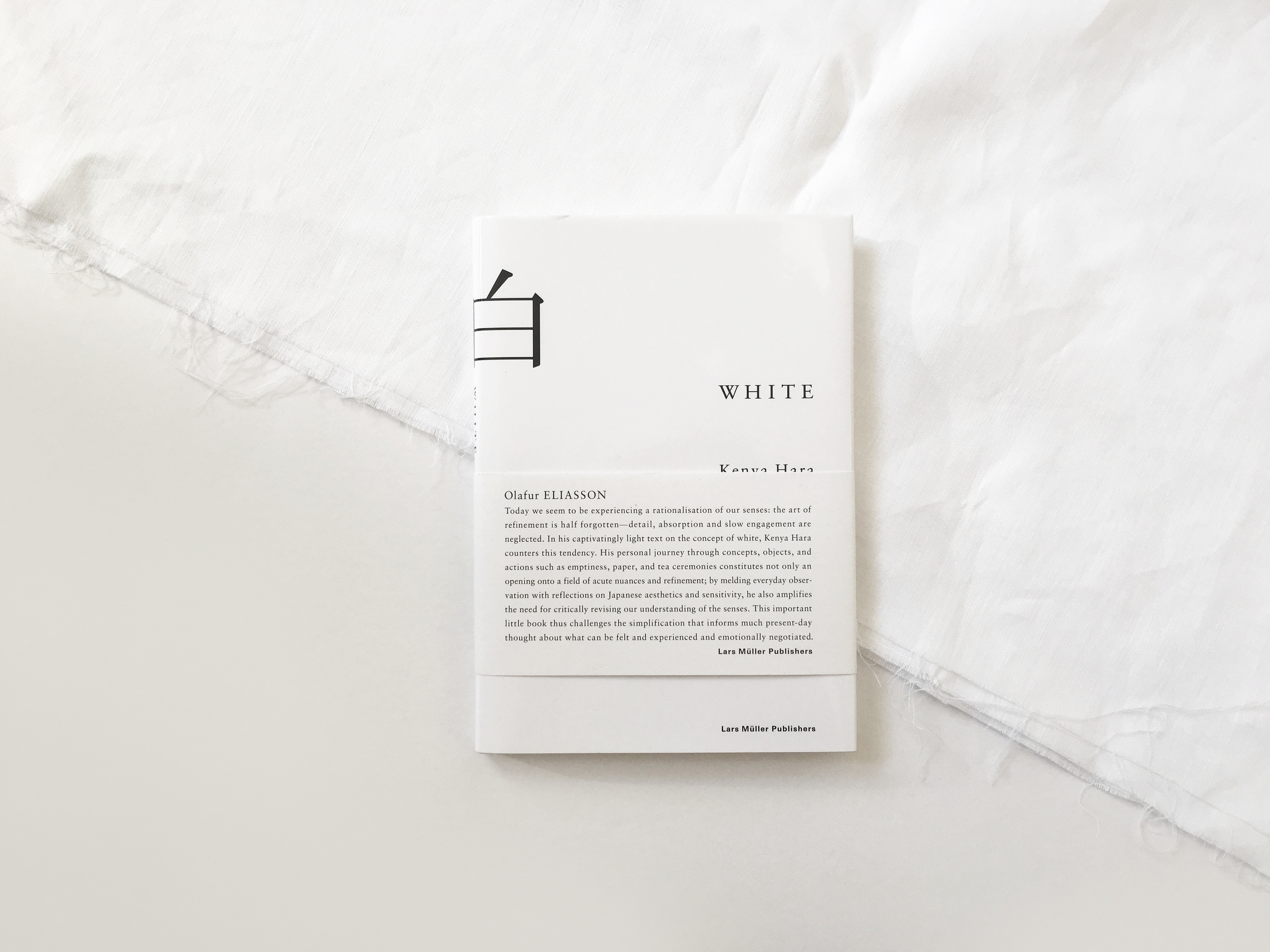

Originally published 11/27/2020 and after my recent trip to Japan in 2024, I’ve revisited the post.

White as a Color

Kenya Hara sees white as a special color. It’s a color that’s only found in the extremes of life and death. In the early stages of life, we see it in milk and eggshells. In the later stages of life, white is found in dead shells and bones. As soon as white appears in the world, it starts losing its whiteness.

“White is delicate and fragile. From the moment of its birth it is no longer perfectly white, and when we touch it we pollute it further, though we may not realize it.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

“According to one of the most prominent experts of kanji ideograms, Shirakawa Shizuka, the Chinese characters for white (白) was modeled after the shape of the human skull. This is supposedly because the image of white held by the people who lived back then was based on the sight of abandoned skulls in the fields, bleached by wind, rain and sunlight.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

Things go from a non-colored state to gaining color, and once it dies, it goes back to it’s non-colored state. Thus, Hara makes the point that we can actually see white as the absence of color. He describes white’s ability to take on the possibility of many colors and states as kizen. Kizen refers to the latent possibilities that exist prior to an event taking place.

“Insofar as white contains the latent possibility of transforming into colors, it can be seen as kizen.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

A manifested form of kizen is a sheet of white paper.

Hara argues that paper’s practical use in history “[was] less important than its imaginative impact. Human beings who come in contact with its latent potential are naturally driven to express themselves.”

A sheet of white paper invokes kizen. The limitless possibility of what that piece of paper can hold is white.

White as a Philosophy

Japanese minimalism is often spoken in context of “less is more” and “simple is best.” These phrases, however, miss the mark of what Japanese minimalism is really about. Japanese minimalism is about expressing “emptiness.”

“The roots of expressions like “simple is best” and “less is more” are subtly different than those that underlie emptiness. Emptiness does not merely imply simplicity of form, logical sophistication and the like. Rather, emptiness provides a space within which our imaginations can run free, vastly enriching our powers of perception and our mutual comprehension. Emptiness is this potential. Therefore, even if someone self-consciously applies a simple geometrical style to his work, or maintains a pretentious silence, he or she cannot grasp the true meaning of emptiness. One must train oneself and build up experience in order to apply that concept efficiently. The ideal that we strive for is the realization of a plan that will evoke the imaginative powers of our audience.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

Emptiness is found in many of Japan’s art and design forms, for example in their architecture, the way they think about space, and even book design and gardens. An example Hara shares is Hasegawa Tohaku’s painting “Pine Trees” (松林図 屏風).

“It conveys the lively image of the trees by intentionally avoiding detailed description, and approach that activates the imagination of its viewers. In short, the paintings very roughness and omission of details awake and our senses.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

Hara uses “Pine trees” as a way for us to understand white as he sees it. By omitting explicit details about the scenery, the painting uses emptiness as a technique to activate the viewer’s imagination.

To better understand emptiness, Hara gives us a history lesson on where Japanese minimalism “started.”

Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436 to 1490) was a shogun who played a lead role in the Onin war. The Onin war resulted in the destruction of many lives and shrines, art, and culture. This caused Yoshimasa to retire and reflect in Higashiyama. He spent his days practicing calligraphy, painting, and performing tea ceremonies. He also started the construction of the Ginkaku-ji, also known as the Silver Pavilion. To Hara, this was the start of a Japanese emphasis on simplicity and emptiness.

Photos I took at Ginkaku-ji in Dec 2023

Hara asks a rhetorical question to us about this culture shift:

“Why did Higashiyama aesthetics put such an emphasis on “simplicity” or “emptiness”? Could a general war-weariness have caused Yoshima and his fellow Kyotoites to look at the world differently? Perhaps. What is more important than such idle guesswork is the fact that Japanese desperately sought beauty in simplicity on their own from this period on, breaking away from foreign influences.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

Hara gives an example of the famous tea room in the Silver Pavilion that was simple in design due to its “scant furnishing.”

“When a host invites his guest into his tiny teahouse for an exchange of thoughts, there is a reason for scant furnishings: one’s imagination expands in uncluttered, simple space.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

The room is like a sheet of white paper, a medium for endless possibility.

This is a concept that’s important to any field, whether it be in business or art. When you start off with white and free yourself of any pre-conceptions, you can invoke clarity. White doesn’t have to be a blank piece of paper or an empty room, it can also appear via seemingly random phenomena, like when Fan Hui played against AlphaGo.

“It’s just when I play AlphaGo, it shows me something. I see the world [differently], before everything [began]. What is real thing inside Go game? Maybe [it] can show humans something we never discover. Maybe it’s beautiful.” - Fan Hui, AlphaGo

“When knowledge and other habitual ways of thinking about things sinks to the bottom of our consciousness, that thing we call “understanding” floats to the surface like pure white paper.” - Kenya Hara, “White”

We see the antithesis of this occur as companies grow larger. Their empty sheets of paper get filled with unnecessary rules, dozens of products, overlapping systems, and room for imagination quickly disappears [1].

Another interesting example of white and emptiness in Japanese culture is found in the design of Shinto shrines. The Shinto shrine is a temple of worship for the Japanese and is designed to have an empty space in the center. This empty space is called Yashiro. Ya means “a roof”, over “Shiro”, which means white. It literally means white with a roof on top of it.

One of the spiritual beleifs for why the yashiro is left empty is to make room for the gods and deities to visit. But it’s also for the person praying; it gives them empty space—literally—to fill with their thoughts.

This may be the reason why prayer in many religions and beliefs take place in a quiet, open space that has minimal furnishing. Whether you look at a church, a mosque, or a temple, white plays a big part in their design.

White in Communication

Hara also talks about white in communication:

“In other words successful communication depends on how well we listen rather than how well we push our opinions on the person seated before us. People have therefore conceptualized communication techniques using terms like the “empty vessel” to try to understand each other better. For example, unlike other signs whose meanings are narrowly determined, symbols like the cross of the red desk in the Japanese flag allow our imaginations to roam free of any boundaries; they are like enormous empty vessels that can hold every possible meaning.” - Kenya Hara, White

Visualizing our minds as empty vessels is a powerful way to make us better listeners and thus communicators.

White

Hara never gives us a methodology for incorporating white into the way we live and do things. Instead, he leaves that part empty. And maybe, that was his intention.

“Wabi-Sabi is a concept derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence (三法印), specifically impermanence (無常), suffering (苦) and emptiness or absence of self-nature (空, kū). If an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi.” - Wikipedia

[1] Probably what’s happening with Google.